I wanted so badly to be a fishing guide.

I spent my first summer, the summer of 1967, the summer I turned 16, working at a small family owned fishing camp on Delaney Lake for room and board, as a camp laborer. I was allowed to take a boat out with Little Stevie every chance I got, to learn the water, to prepare to guide.

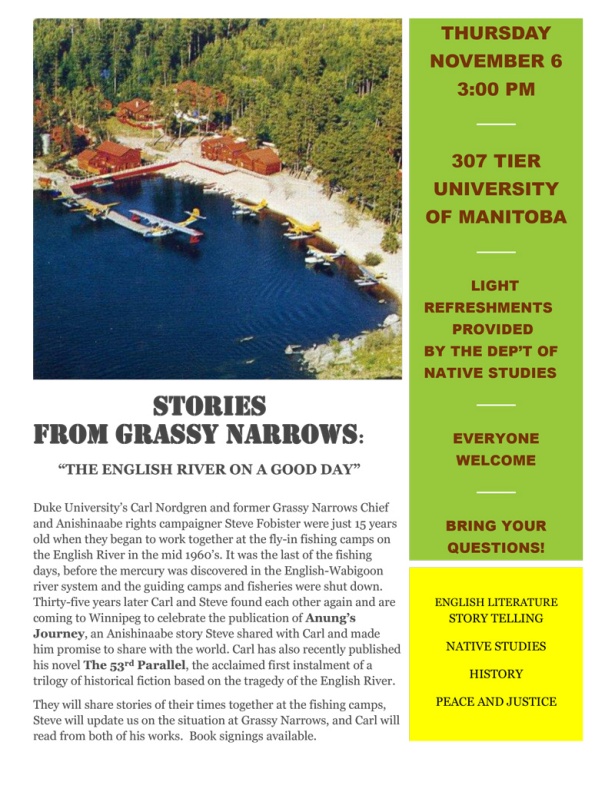

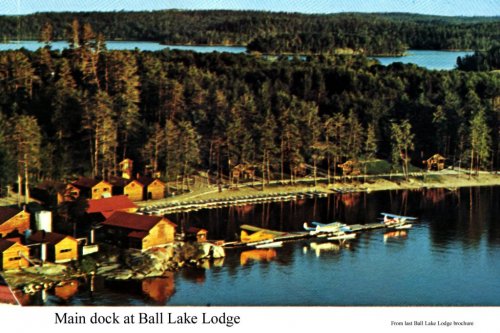

The second summer I moved to a much bigger fishing camp and Barney Lamm, the owner of Ball Lake Lodge, began to include me in the guide pool as “the number three guide in a three boat party.” When six businessmen came in a group for their three or four day fishing adventure, they would need three boats–two guests per boat. So two guests would go out with Joe Loon, two more with Matthew Beaver, and two with me. The idea was I should always keep one of the other boats in sight during the morning fishing for walleyes, that I would meet them at shore lunch, and then we’d fish for northern pike or smallmouth bass in the afternoon, all part of my continued apprenticeship, and I loved it.

But by the time I guided my second party of guests as an apprentice I began to suspect that something was wrong, that perhaps my guests weren’t pleased with me guiding. I hoped it was my imagination, but then, after shore lunch with my third party of guests, it became very clear that guests felt let down with me as their guide…I watched as the guests argued about whose turn it was to be stuck with the kid who looked more like their paper boy than a fishing guide.

A trip to the Canadian wilderness was to be a grand adventure for these men, and I didn’t fit the story of what that adventure looked like.

So I decided it was time to declare the experiment a failure, that I couldn’t be the source of their disappointment, and prepared to tell Barney I had to go home to make some money for college.

How different my life would have been if I hadn’t first checked in with one of other white guides who worked there, David King, a man in his late 20’s, from Kenora, the frontier town where guests boarded float planes on their journey to camp. I asked him how he handled his guests’ disappointment when they realize they aren’t going to have an Ojibway guide. He told me he never experienced this disappointment I was describing and then we saw I was wrong–I wasn’t a disappointment because I wasn’t an Indian; I was a disappointment because I wasn’t of this place…I wasn’t in anyway authentic.

That’s when David invited me to his cabin after supper, gave me my first beer, and told me that I was now Carl Nordgren, a Canadian bush boy, born and raised in Williams Creek on nearby Lac Seul. Then he decided I was raised by my grandfather, a locally famous musky fisherman, and that I played Canadian 12 man football in high school, and with my curly and nearly black hair, my nickname was the “Black Swede.”

I washed down the idea with a second beer and thought, okay, maybe this could work. I sure wanted it to.

So I didn’t say anything to Barney about leaving, and waited until I was given my next ‘3 boat party’ guide job, and I introduced myself as Carl from Williams Creek.

And it worked. The guests began to follow my directions more carefully. We caught more fish. My tips were better–20 dollar bills replaced 10’s. I said little, for fear of getting tangled in too many stories, but it was clear my guests were enjoying the trip much more.

And it worked for a second group of guests. Then a third. In fact it worked so well with the third guests that our fishing was spectacular one day. In the morning we caught more fat walleyes than any other boat. And in those days anything over a 15 pound northern pike was considered a great success and we caught two just over 20 that afternoon.

So that night, in the bar in the lodge after supper, and unbeknownst to me, my guests were bragging to all who would listen about what great fishermen they were. Barney heard them and apparently the conversation went something like…

Barney: “Not bad for a kid from Chicago.”

My guests:”No, no, Carl’s from Williams Creek.”

Barney: “I only have one white guide named Carl, and he’s from Chicago.”

When my guests came down to the dock for the next day–fortunately their last day–they didn’t tell me what they had learned. They acted the same as before, except now they kept asking me more questions, about growing up in Williams Creek, and what it was like to play on the bigger football field with 12 men, and about my grandfather and his musky fishing. And I answered each question…later I saw that they had given me a shovel and urged me to dig a deeper and deeper hole.

So we fished all morning, had shore lunch, and were half way through the afternoon of fishing when the guest in the bow of the boat leaned around his friend and looked me in the eye (he’s 50ish, I am not yet 17) and said “Nordgren, you are one lying son of a bitch, aren’t you?”

“What are you talking about, sir?”

“Barney told us last night that you’re from Chicago, and all the stories you’ve been telling us are lies.”

Well ladies and gentlemen, I began to cry. I was so ashamed. I tried to explain why I had done what I had done, and considering that they had just spent 4 days in a boat with someone who was lying to them the whole time, they were very gracious.

That night I knew I had to resign. I figured I had betrayed Barney’s trust and that he would be very upset that I had lied to his guests.

His reaction was unexpected. He explained to me that the major complaint, the only regular complaint, he gets from guests is that the Ojibway guides won’t tell the guests stories about this place. The older guides, the men in their 50’s and 60’s, only spoke English well enough to communicate the days’ logistics and plans, not maintain any sort of narrative. And the younger guides, the men in their late teen and 20’s…well, it was the late 60’s, when people of color were defining new relationships with the white man’s power structure, and these guides weren’t eager to be entertainers–they didn’t want to do more than the basics of the job.

So Barney told me that now that he knew my strategy for pleasing guests he would support it, as long as I made a concerted effort to learn the stories of the Ojibway and the English River, and of Ball Lake Lodge, and share them with my guests.

I said yes! And I continued being an apprentice guide that second summer, and was a full fledged guide for two more summers after that, telling stories from the back of the boat.